Edgar L. Hewett’s Dream

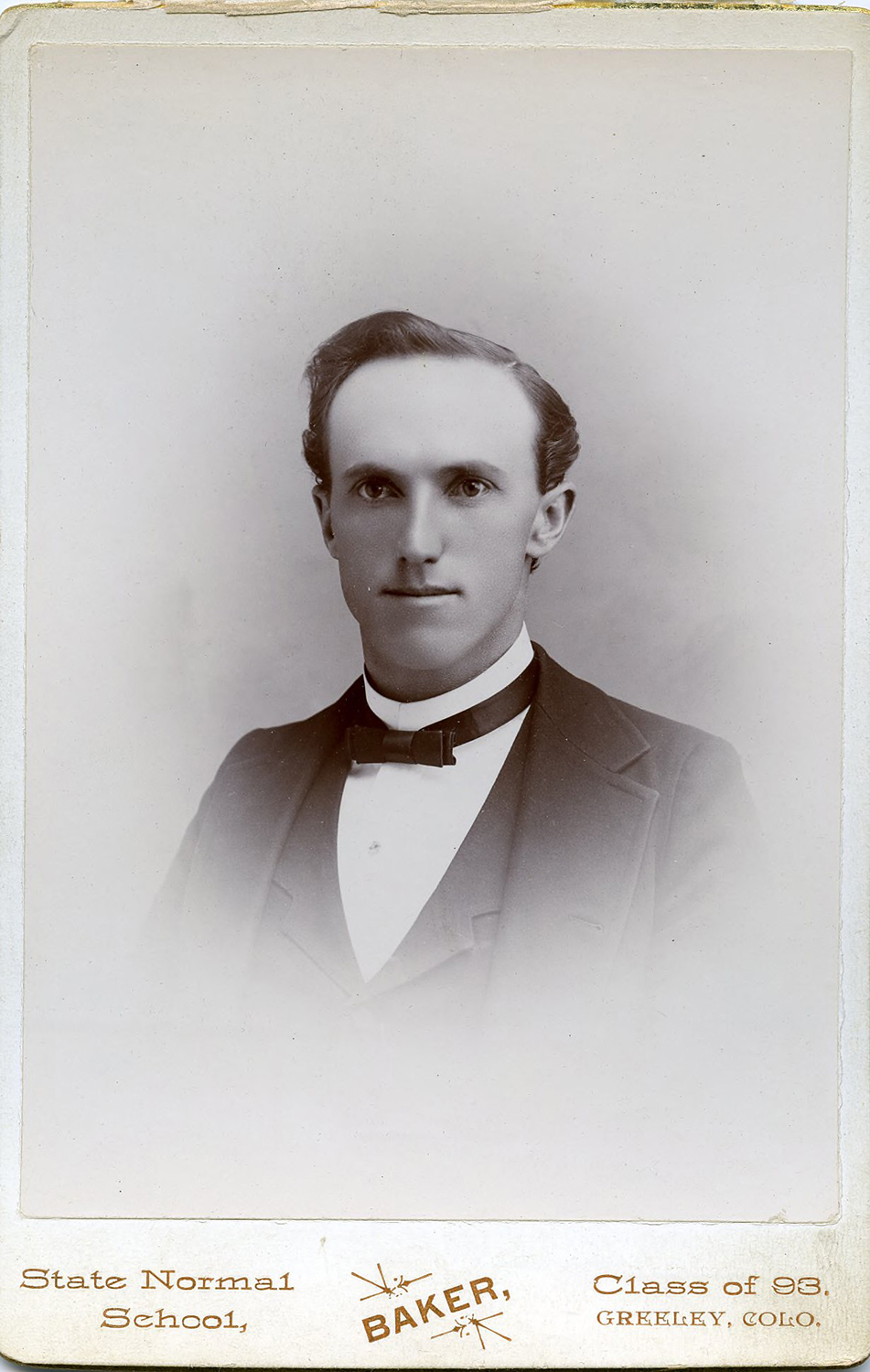

On February 19, 2009, the Museum of New Mexico celebrated its 100th anniversary. Established three years before New Mexico became the forty-seventh state, the Museum’s early history and the trajectory for its later development can largely be attributed to one man—Edgar L. Hewett. An assertive and energetic individual known as El Toro, Hewett was a renowned archaeologist at the time and is still an esteemed figure today. In addition to his considerable involvement in directing the new museum and founding other institutions, Hewett always kept an abiding and active interest in archaeology. He worked tirelessly to promote Southwest archaeology to the same level of public interest as that of the classical archaeology of Europe and the Near East. At the same time, Hewett’s powerful personality led to professional conflicts and set the stage for eventual challenges to his influence.

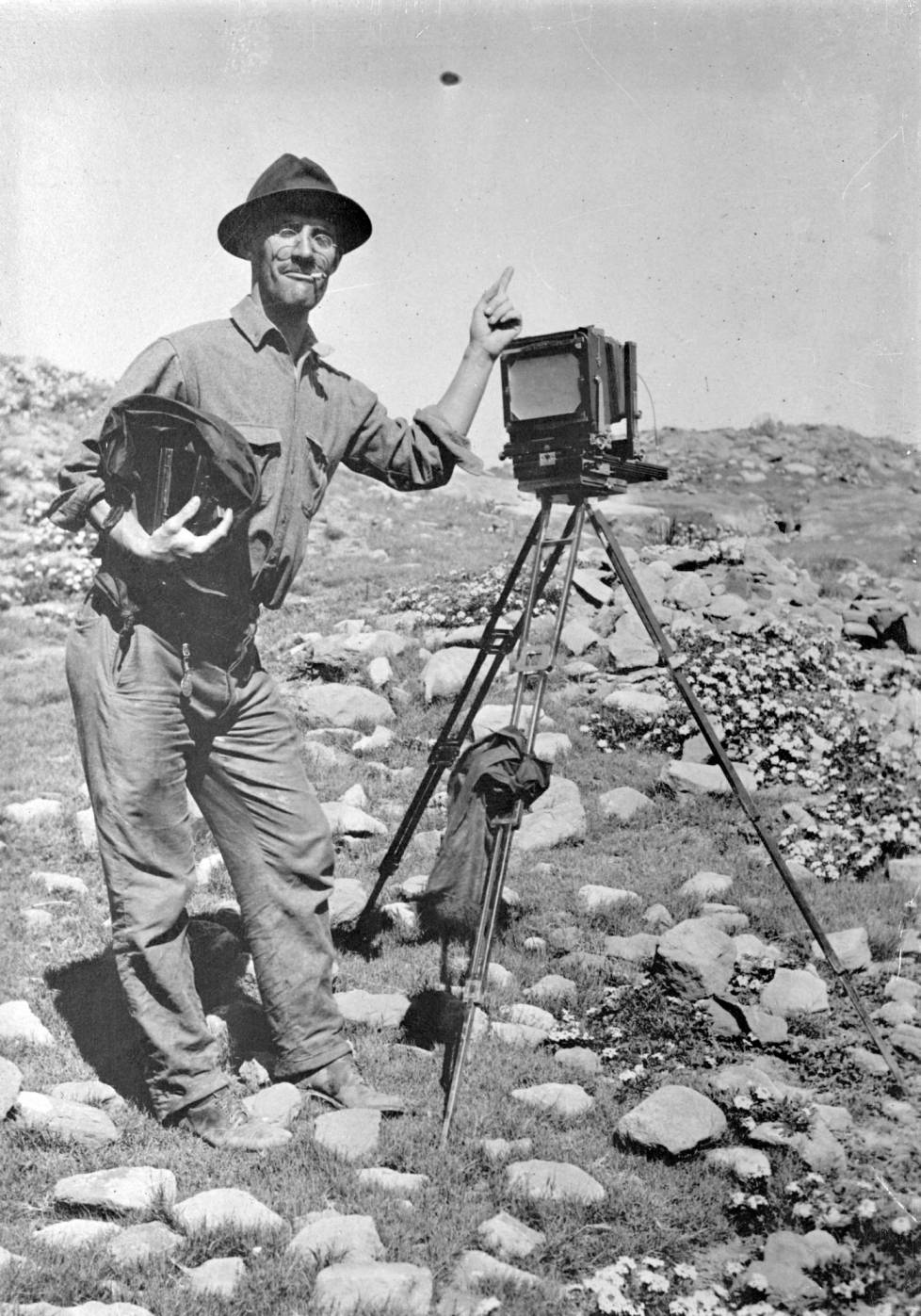

As president of the New Mexico Normal School (now Highlands University) until 1903, Hewett was dedicated to archaeological research and the protection of sites. His work at Mesa Verde, funded by the Archaeological Institute of America, helped prove the importance of the site and the need to preserve the nation’s archaeological resources. As a result of his efforts, the 1906 Preservation of American Antiquities Act was passed, and Mesa Verde became a national park. In 1907 and 1910, Hewett excavated Puye cliff dwellings (on the Pueblo of Santa Clara) and then traveled through the Casas Grandes region of northern Mexico to gain a broader perspective on the prehistory of the Southwest. He returned to Santa Fe to establish the new headquarters of the School of American Archaeology (known later as the School of American Research [1917-2007], and now as the School for Advanced Research) for the Archaeological Institute of America. The new school occupied the Palace of the Governors on the Santa Fe Plaza and operated the Museum of New Mexico, established by the territorial legislature in 1909. Hewett’s excavations at Puye became the basis for the first exhibit at the Palace of the Governors.

Hewett’s students would later make a who’s who list of American archaeologists. He sent his first students, Sylvanus Morley, A. V. Kidder, and John Gould Fletcher, to investigate in the Mesa Verde region. Morley later studied the Mayas. Kidder excavated Pecos Pueblo and developed an early overview of Southwest prehistory. Two of his former faculty at the Normal School, Kenneth Chapman and Jesse Nusbaum, also joined Hewett’s staff. Hewett soon expanded the school’s research into Guatemala, and shortly afterward, more students, including J. P. Harrington, Neil Judd, and Earl Morris were accepted. Hewett later helped further their careers, and the science of archaeology, by finding jobs for them in the federal government, museums, or universities.

To maintain a leadership role in New Mexico archaeology, anthropology, and history, the Museum of New Mexico began publishing El Palacio in 1913. The journal printed seminal articles and scholarly research that frequently remain cited. As the school and the Museum of New Mexico grew, Hewett became less dependent on the Archaeological Institute of America, and, in 1917, the School of American Archaeology, a new private corporation, was formed. Hewett also encouraged visiting and local artists to use studio space in the Palace of the Governors. Their interactions with the steady stream of archaeologists and historians flowing through the Palace helped consolidate the image of a Santa Fe architectural style that defines the downtown area today.

As director of three organizations, Hewett was busier than ever but returned to the Casas Grandes region in 1922 for preliminary planning of an archaeological project. Hewett never found time for the project, and it was not until 1995 that the museum, through the Office of Archaeological Studies, initiated a Casas Grandes project.

A Challenge to Hewett: The Laboratory of Anthropology, Inc.

In 1924, a tour of the Southwest by John D. Rockefeller Jr. led to the establishment of a new institution, also concerned with Southwest archaeology. One of Hewett’s original staffers, Kenneth Chapman, noted for his studies of Southwestern pottery, guided Rockefeller around Santa Fe, stirring Rockefeller’s interest in Southwestern Indigenous culture. Three years later, Rockefeller funded the establishment of the Laboratory of Anthropology, Inc., a private independent institution with strong ties to academia but lacking a connection to the Museum of New Mexico and the School of American Research. The new research center opened its doors in 1931. Hewett’s former protégé, Jesse Nusbaum, became its director. Kenneth Chapman, perhaps also wishing to escape Hewett’s dominance, moved himself and his staff to the new institution. Despite its auspicious beginnings and the great hope for a regional research facility, the Great Depression affected dependable funding for the Laboratory of Anthropology. All funding eventually falted, leading to its incorporation into the Museum of New Mexico. However, the establishment of the Lab was a direct challenge to Hewett’s influence, and the loss of some of his talented staff was undoubtedly a blow.

The Laboratory of Anthropology worked actively in the four branches of anthropology: archaeology, ethnology, linguistics, and physical anthropology. A series of summer field sessions were led by eminent anthropologists such as A. L. Kroeber, Leslie Spier, Ruth Benedict, Leslie A. White, Ralph Linton, A. V. Kidder, Fay-Cooper Cole, Frank H. H. Roberts, William Duncan Strong, Emil Haury, and Edward Sapir. Meanwhile, Dr. Harry P. Mera, formerly a public health official, became curator-in-charge of the archaeological survey program. The goal of the survey was to record all archaeological sites in the Rio Grande drainage and develop reference pottery collections. The site numbering system developed by Mera is still used today. When Mera retired in 1946, 2,400 sites were on record. Today, the number is about 210,000. Another early major effort by the new laboratory was the Dendro-Archaeological Survey, which sought to develop a useful chronology for dating sites. Anna O. Shepard also wrote her major contribution to archaeology, Ceramics for the Archaeologist, while working at the Lab.

As the Laboratory of Anthropology was being established in 1927 without Hewett’s support, Hewett worked with University of New Mexico president James Zimmerman to establish an anthropology department at the university. The department drew hundreds of students, leading Hewett to recruit more faculty. He then started a series of important summer field schools, which trained another generation of Southwestern archaeologists.

The Museum of New Mexico/School of American Research and the Laboratory of Anthropology fueled their professional competition throughout the 1930s. In reaction to the newly established Laboratory, Hewett expanded his archaeological staff. Prompted by the Lab’s new emphasis on collecting Indian art, Hewett also hired Bertha Dutton, an archaeologist, to direct the Museum’s new Department of Ethnology. Stanley Stubbs and W. S. Stallings, who had joined the School/Museum staff in the 1920s, went to the Laboratory of Anthropology in 1933. They excavated a large Ancestral Pueblo Santa Fe village known as Pindi Pueblo and defined the Pueblo III period in the region. Betty Toulouse became a Lab employee in 1934 and later became the curator of collections. Marjorie Lambert arrived at the school in 1937, after working with Hewett during a University of New Mexico field school at Chetro Ketl in Chaco Canyon and conducted many important excavations in the following years. In 1938 and 1939, H. P. Mera and E. T. Hall surveyed the Gobernador area and excavated sites for the Laboratory of Anthropology. Mera also worked out a chronology for Pueblo pottery and published ten important monographs on his findings that are still used today.

Post-World War II Integration

In 1947 the Laboratory of Anthropology, unable to find a dependable source of income, became a unit of the Museum of New Mexico. With a postwar boom in economic activity, Lab archaeologists were instrumental in redefining the country’s treatment of archaeological sites. In 1950, as oil and gas fields were developed in New Mexico, former Lab Director Jesse Nusbaum, then with the US Department of the Interior, cited the 1906 Antiquities Act and convinced oil and gas producers to locate and study archaeological sites affected by their projects. For the next three years, the Laboratory of Anthropology and the Museum of Northern Arizona worked together to record and excavate those endangered sites.

As the oil and gas project wound down, Fred Wendorf, the pipeline project director, witnessed the partial destruction of Howiri, a Rio Grande Classic pueblo on the Rio Ojo Caliente, by Highway Department bulldozers. Wendorf, as Director of the Lab, convinced the Museum of New Mexico director, Boaz Long, to involve the Museum in a highway salvage program, and the first excavations took place near Gallup in 1954. The program was formalized with the New Mexico Highway Department in 1956. Also in 1956, with the help of notable New Mexicans Senator Dennis Chavez and Representative John Dempsey, the US Congress passed the Federal Highway Salvage Act. The law was a result of Wendorf’s personal efforts and the relationship between the Museum and the Highway Department in New Mexico.

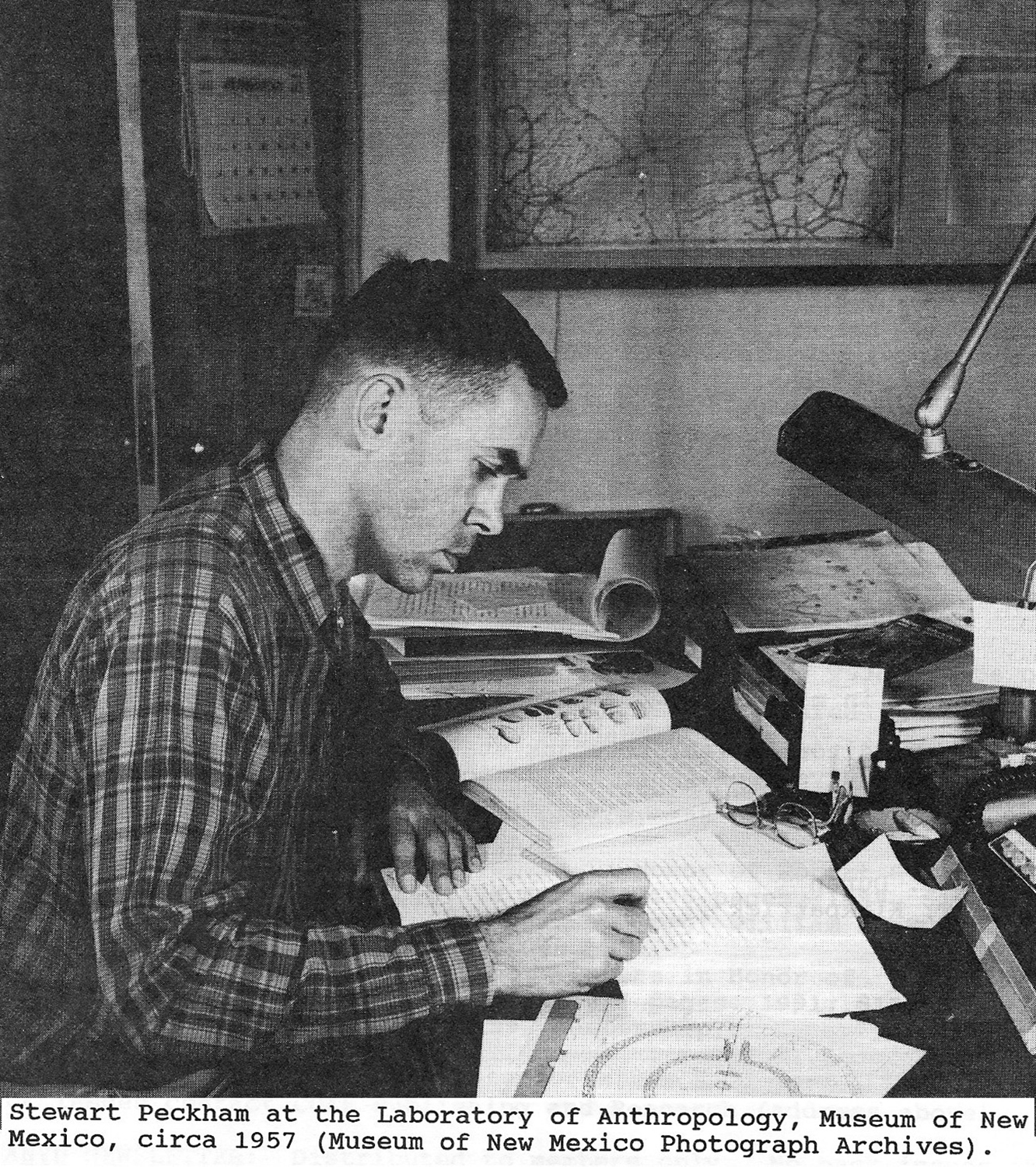

The Lab staff grew as the highway program expanded, and Wendorf hired Stewart Peckham to assist. In 1955, the Highway Salvage Program became a separate department within the Museum of New Mexico. The first two volumes of resulting research appeared in 1956. Since that time, over 800 reports on highway-related archaeology have appeared. The Museum developed an experimental training program in salvage archaeology in 1960, funded by the National Science Foundation and cosponsored by the Fort Burgwin Research Center.

In 1959, the School of American Research and the Museum of New Mexico became separate entities. The link between the state and private institution created difficult legal issues that could be resolved only by separating the two organizations. During the 1960s, the Laboratory of Anthropology conducted several large archaeological projects related to dam-construction projects, including Abiquiu, Cochiti, Galisteo, and Navajo Reservoirs, as well as large highway projects like the one around Prewitt. At the time, there was no other institution in New Mexico capable of undertaking these large projects. The Navajo Reservoir project alone required ten years of work.

By 1973, over 6,000 sites had been recorded as part of the Highway Salvage Program. Most of these were smaller sites, previously ignored by archaeologists. Prior to the 1950s, the archaeology of New Mexico had mostly been determined from studies of large and widely scattered sites such as Puye, Pecos, Jemez, Zuni, and those in the La Plata, Mimbres, and Chaco Canyon regions. Study of these smaller sites began to fill in the gaps in archaeological knowledge. The Museum archaeologists of the 1950s and 1960s also began to use multidisciplinary approaches, drawing upon the expertise of geologists, petrographers, botanists, palynologists, and ecologists.

The Growth of Cultural Resource Management

By the mid to late 1970s, much of the Laboratory of Anthropology staff was dedicated to cultural resource management studies. An outgrowth of the pioneering efforts of the Museum of New Mexico, the Lab became a model for the rest of the nation. Much of the Lab staff was continually in the field, studying and excavating sites in advance of development.

In 1979, the highway salvage program expanded beyond highway salvage projects. Under the direction of David H. Snow, it was reorganized as the Research Section of the Laboratory of Anthropology. The change guaranteed that the program had a dynamic role in the active profession of archaeology, that it continued to add to the Lab’s research collections, and that publications on projects continued to be produced. By 1984, the Research Section had outgrown its location in the Laboratory of Anthropology. Along with the Laboratory’s archaeological research collection of almost ten million artifacts, the Research Section moved to new offices in downtown Santa Fe.

The Research Section continued to grow in the late 1980s. In 1989, several new programs were added to meet the need for specialized analysis: an archaeomagnetic dating laboratory, ethnohistorical research, and an osteological laboratory. On July 1, 1990, the Research Section was organized as the Office of Archaeological Studies, separating the administration of cultural resource management from the Laboratory of Anthropology though maintaining its organizational connection. David A. Phillips became the first director and departed in 1991.

In 1991, Tim Maxwell became the director and in 1993, the Office of Archaeological Studies became a new Museum of New Mexico division. Since 1990, the Office of Archaeological Studies has expanded its educational outreach programs, increased the number of grants it receives for research, worked with the public to develop a foundation support group, developed new ethnobotany and dating laboratories, and twice won national awards for its outreach efforts. In 2004, the Office and the New Mexico State Highway and Transportation Department recognized the fiftieth anniversary of what is fifty years of the first cooperative Highway Archaeological Salvage Program in the United States.

Eric Blinman was named director in 2005 and in 2010 moved the office into a new building – the Center for New Mexico Archaeology. It took 12 years to obtain the funding, but the wait was worth it. Laboratory workspace was expanded, and private space was created for Tribal members interested in examining and discussing prehistoric and historic objects. The objects reside in a portion of the Center shared with the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture’s Archaeological Research Collections. The education program was further developed and Blinman also strengthened the Museum of New Mexico Foundation, Friends of Archaeology support group, as well as the Office volunteer program.

Today, the Office of Archaeological Studies continues the advancement and use of archaeological science. A new ground-breaking method of radiocarbon dating that doesn’t require the destruction of an object was developed. Also, non-destructive ways of chemical analysis are available. Experiments with ceramic technology are helping archaeologists understand prehistoric pottery-making while new field techniques are constantly evaluated. Much of this research is a joint effort between staff and volunteers.

Timothy D. Maxwell, Ph.D., Director Emeritus

* I would like to thank the late Stewart Peckham for his comments on this brief historical overview.